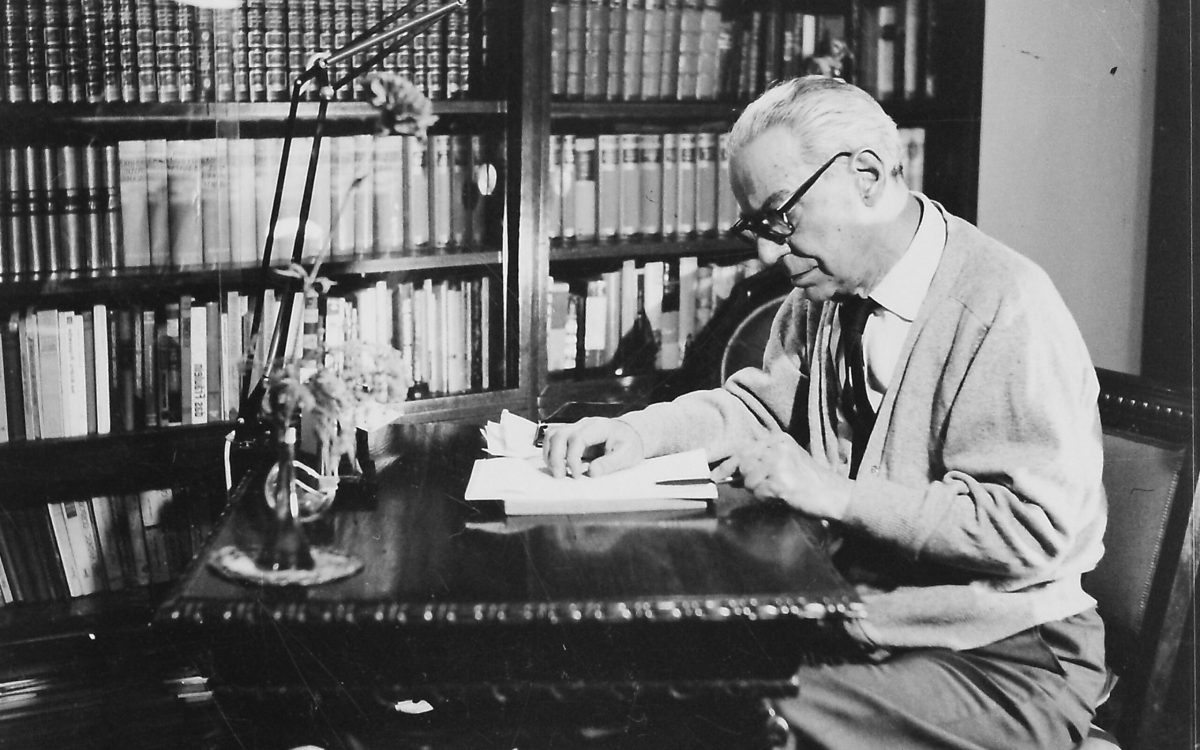

In 1943, the German occupiers approached Ivo Andrić with a request. A document from the archives of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts (SANU) reveals how the future Nobel Prize winner responded.

In January 1944, Ivo Andrić received a letter from Vienna that could have put him in danger. The sender of this letter, dated December 28, 1943, was a representative of the publishing house “Wiener Verlag”, who made a request to Andrić: “Wiener Verlag,” he wrote, planned to publish a new edition of Andrić’s short stories, originally published in German in Hitler’s Germany in 1939. The publisher intended to obtain the necessary permission to use rationed paper.

At that time (as in the early post-war years), paper was strictly rationed, and publishing houses could obtain it only with government approval. In addition, the publisher wanted to include Andrić’s short story “Anikina vremena”, which had not yet been translated into German.

“Before we take the necessary steps with the authorities for (…) publication,” the letter read in a respectful tone, “we would first like to receive your principled approval for our plans (…) We eagerly await your consent so that we may send you an appropriate contract with our publishing house (…)”

FIND OUT MORE IN ENGLISH:

A REAL DANGER

What may seem harmless today was, at the time, a matter of life and death. In the final phase of World War II, under German occupation in Belgrade, Andrić faced a decision that could determine his fate.

As a matter of principle, he had decided not to publish a single sentence as long as his country remained under Hitler’s occupation. But how could he refuse the occupiers’ request without raising suspicions among the Nazis? The danger was real. Many had disappeared into the Gestapo’s basements or German concentration camps, with little hope of survival. The Nazi machinery of destruction could have swallowed him too.

There were at least two other known cases from the war years where Andrić faced similar dilemmas and refused to publish under German occupation.

The first occurred in September 1942, when he sent a now-famous letter from Sokobanja to Svetislav Stefanović, then head of the “Serbian Literary Cooperative”, a position he held under the German occupiers. In the letter, Andrić firmly declined to participate in an anthology of Serbian short stories, which was to be published with the occupiers’ approval. He wrote:

“Under normal circumstances, I would have accepted your invitation. Today, however, I cannot, because in the current extraordinary circumstances, I will not and cannot collaborate on any publications, whether with new works or previously published ones (…)”

The second case occurred in spring 1943, when Svetislav Cvijanović, Andrić’s longtime publisher, published several of his works without his knowledge. Upon discovering this, Andrić reacted sharply, even involving a lawyer, and successfully demanded the books be withdrawn from circulation.

However, it had been relatively easy for Andrić to say “no” to Stefanović and Cvijanović, as they were his compatriots—though one served the occupiers. The 1944 request from “Wiener Verlag” came directly from the occupiers themselves. Unlike in Nazi-controlled Croatia and fascist Italy, where publishers simply printed his works without permission, in this case, the German publisher had formally sought his approval.

By early 1944, Germany’s military situation had turned against them. The Wehrmacht and SS still controlled much of Europe, but they were under immense pressure. The Allies had taken Sicily, landed in Italy, and were preparing to invade France. Soviet forces were advancing from the east, while American and British bombers were turning German cities into rubble. Hitler’s forces were growing desperate.

Despite this, the occupiers remained in Belgrade, and Hitler’s regime was becoming increasingly paranoid and ruthless as the war neared its end. There was a real risk that if Andrić refused too bluntly, he could be labeled a communist or a resistance sympathizer, leading to his arrest.

Had that happened, the world might never have known “The Bridge on the Drina”, and literature would have been deprived of a future Nobel laureate from Bosnia.

A MASTERPIECE OF DIPLOMACY

So what did Andrić do?

First, he remained silent. He did not rush to respond. He likely took his time crafting the perfect answer because his reply is a masterpiece of diplomacy, with every word carefully chosen. It demonstrates why Andrić had built a successful diplomatic career before becoming a full-time writer. He had mastered the art of saying “no” in a way that sounded like “yes.”

In his letter to the editorial board of “Wiener Verlag”, dated February 1, 1944, Andrić thanked them for their “kind offer” and then wrote:

*”Regarding the new edition of my short stories that you are planning, I feel it necessary to inform you of my following principled position on the matter.

After more than thirty years of literary work, I have reached a personal turning point that could give my writing a new form and direction. In relation to this, I am currently working on a new book where all these new ideas should be expressed.”*

This was true—during the occupation, Andrić had indeed used his time to write “The Bridge on the Drina,” “Bosnian Chronicle,” and “The Woman from Sarajevo”, the works that would later bring him global fame.

Then came the key part of his response:

*”At this stage of my intellectual and artistic development, I would not want any of my earlier works to be published before I complete the book I am currently working on.

For these reasons, while once again thanking you for your kind proposal, I kindly ask that, for now, you refrain from printing a new edition of my short stories, as well as the story ‘Anikina vremena.’ As soon as my new work—which I hope to finish soon—is published, there will no longer be any objections on my part to reissuing my earlier works.”*

Of course, this apparent agreement was nothing more than an elegant deception. Andrić deliberately avoided specifying a date, merely stating that he “hoped” to finish his work “soon.” But like millions of others in occupied Europe, he was counting on Nazi rule ending before that happened.

To ensure there was no misinterpretation, Andrić ended his letter with the following reassurance:

*”Firmly believing that you will fully understand this personal, deeply important stance of mine—one based on creative and psychological motives—I once again ask that you temporarily set aside the matter of publishing my short stories.

Thanking you in advance for your kind consideration, I remain,

With my highest regards,

Ivo Andrić.”*

A LITTLE-KNOWN DOCUMENT

The original letter, along with its Serbian translation, is preserved in the “Ivo Andrić Personal Collection” at SANU. Although it was mentioned in a 1980s catalog, it has remained largely unknown to the wider public.

This diplomatic refusal in 1944 played a crucial role in Andrić’s post-war career. When the Germans were replaced by the communist regime in Belgrade, Andrić’s firm refusal to collaborate with the occupiers worked in his favor.

Unlike Svetislav Stefanović, who was executed as a collaborator in 1944, Andrić went on to live three more decades as a celebrated author—all because he made the right decision at the right time.

MORE TOPICS:

LOVE AND BETRAYAL LED HIM TO THE BLUE TOMB: The tragic end of Vladislav Petković Dis!

Source: Mihael Martens (tekst je prvobitno objavljen u srpskom izdanju magazina Newsweek)

Foto: Wikimedia Creative Commons