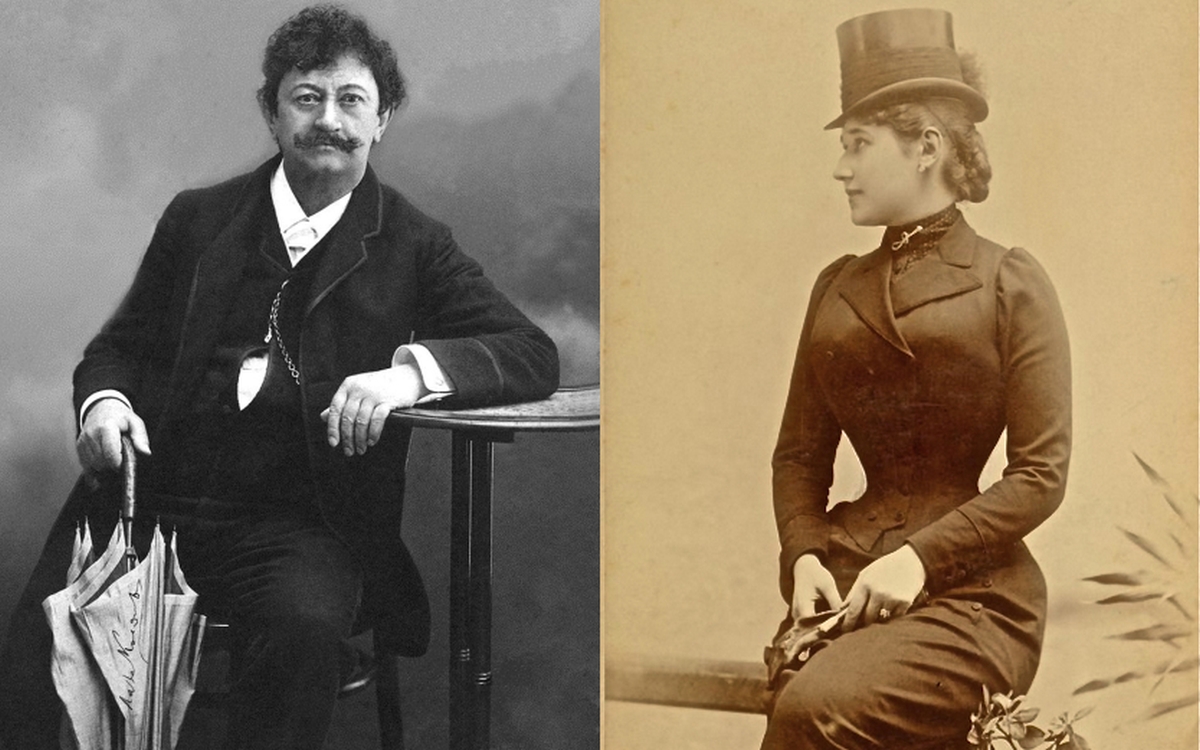

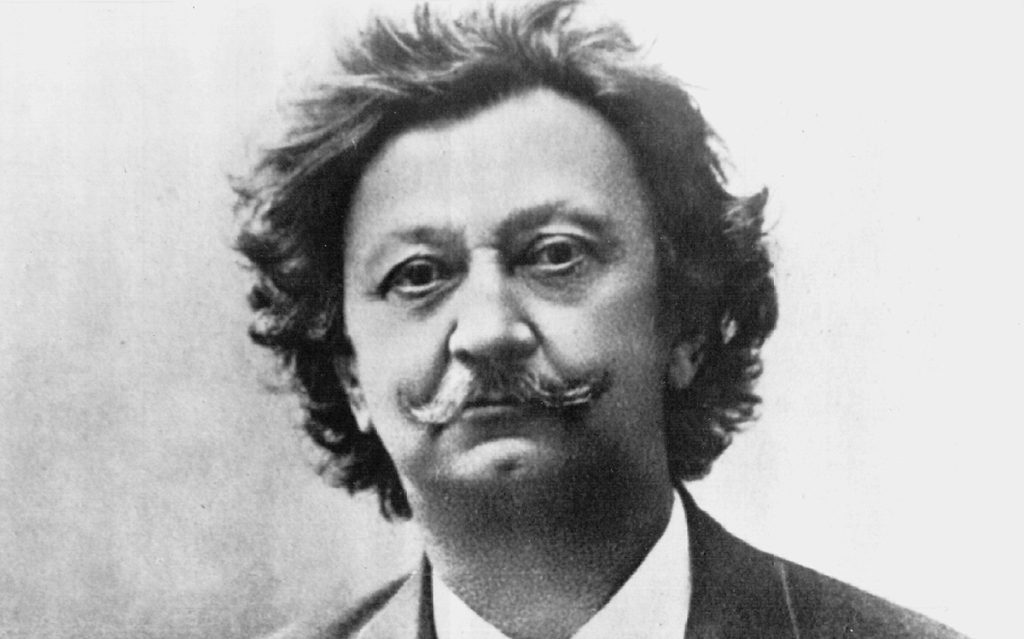

After seven years spent in Cetinje, Montenegro, Laza Kostić returned to Bačka in the spring of 1891. On the estate of the wealthy Serbian Dunđerski family in Čeb, in the summer of 1891, he first met Jelena-Lenka, the young, but already grown-up, beautiful, educated, and intelligent daughter of his host, friend, and later best man, Lazar Dunđerski. He was almost thirty years older than her (according to the entry in the baptismal register of the Srbobran Epiphany Church, Lenka was born on October 26/November 7, 1869).

As much as Kostić was enchanted by her, Lenka, who was versatile and youthfully curious, must have been attracted, at least intellectually, by the unique and unusual poetic presence of Laza Kostić in her vicinity. She was resolute and independent; besides her mother tongue, she spoke French, German, and Hungarian, was an excellent horsewoman (she also drove light carriages herself), a skilled pianist, and had a nightingale voice, with inclinations toward painting and theatre. She also did not lack kindness and thoughtfulness, nor the skill of making reasonable choices (up until then, as Laza Kostić wrote, she had rejected an entire army of suitors).

The letter he sent to Nikola Tesla in June 1895, in which he recommended her as a wife to the already famous scientist, speaks of his infatuation with this girl, perhaps to banish her from his thoughts and dreams: “The girl I intended for you is capable of overcoming any misogyny. I think she would revive even the dead, not only the dead Don Juan but also the dead saint…”

Laza Kostić, reliably, was not, at least not in those years, when it came to women, a viveur, nor could a real, tangible woman particularly inspire him, neither in life nor in poetry. However, here, perhaps for the first time, he encountered an ideal in which all the qualities he himself strived for were intertwined—an almost perfect harmony of beauty and mind, tempting flesh and sparkling spirit—and the seasoned aesthetic, the author of the treatise “The Basis of Beauty in the World,” could not remain indifferent. Lenka simply happened to Laza Kostić.

One can only guess that Lenka, at least for a moment, was not indifferent to him (in one of the preserved entries from the secretly kept diary in which he noted her appearances in his dreams, he wrote in French: Splendid with youth and beauty, more blonde than you were, almost transparent, you looked at me with that look full of desire, promise and devotion, that look that encourages, calls, almost challenges, the look with which you looked at me in this world only once, at a moment remembered for all eternity, when you looked at me thinking I didn’t see you. Oh, that immortal look! That inexhaustible source of desires, which fate has condemned to remain unsatisfied in this world!).

But the insurmountable chasm between them—the difference in age, the close friendship with her respected father, the immeasurable disproportion in material status—caused bitter resignation in the poet, beneath which one could sense the subconsciously desired hint of the depth of his volcanically boiling feelings, poorly disguised by layers of reason and self-irony in the verses of the poem, intended for Lenka’s keepsake album, which he wrote in Krušedol in 1892, and which he published under the name “To Miss L. D. in a memento” at the beginning of 1895 in the Sarajevo “Nada.”

Regardless of the later, often superficial, mystifications of their relationship, the conclusion that the burgeoning feelings of strong platonic love (it certainly could not have been otherwise) for Lenka Dunđerski accelerated and broke his decision to marry (I wisely fled from happiness, mad) is not out of mind. The fact that marrying Julijana Palanački and moving to Sombor was not yet on the horizon is evidenced by the official request he sent in 1894 for admission to the municipal population of Krušedol. He made a decision about this, as will be seen, quickly and suddenly (the wedding, by the decision of the bishop, was also exempted from the obligation of the thrice-repeated announcement).

Laza Kostić and the wealthy Sombor heiress Julijana Palanački were married on September 22, 1895, in the St. George’s Church in Sombor, 25 years after their first meeting and Julijana’s words to her friends and relatives that she would either marry him or not marry at all, and 11 years after their failed first engagement, before Kostić’s departure for Cetinje in the spring of 1884.

Immediately after the wedding, Kostić set off with his wife on a honeymoon trip to Venice, where, perhaps from the terrace of the “Bauer-Grünwald” or “Grand Bretagna” hotel, he observed the Grand Canal and the Santa Maria della Salute church (Milan Kašanin). Laza Kostić had sung about this famous baroque church 17 years earlier in his poem “The Doge is Marrying!”, regretting that the pines of the Slavic mountains had been cut down for its construction (it was built between 1631 and 1681 according to the idea and designs of the architect Baldassare Longhena). Fourteen years later, this church would once again become the fundamental and sublime poetic motif and refrain of his final and greatest poem of the same name.

Upon returning from their honeymoon, Kostić’s first misunderstandings with his wife and her mother began. A nonconformist, somewhat anarchic, and unaccustomed to respecting and understanding the established order of the Palanački bourgeois home (with his aristocratic-negligent manners, Laza did not fit into an ordinary bourgeois house where prosaic people live, his doctor Dr. Radivoj Simonović wrote), Kostić left his wife’s house only a few days after returning from the honeymoon and went to Novi Sad, and then, again, to the Krušedol monastery, where he would stay for almost the entire following year. During this time, he maintained constant correspondence with his wife, most often discussing his status in the marriage and family.

By a twist of fate, a few days after he left Sombor, he received news that his young goddaughter Lenka Dunđerski had suddenly died of typhus fever in Vienna. He could not hide his sadness and despair even in the letter to Julijana: Not even my own sister was dearer to me than her. You can imagine how I feel. The whole world is black to me.

From that time on, he began to show signs of otherworldly obsessions with this deceased girl, who visited him in dreams, which he wrote down in French, so that these hallucinatory records would later be poured, as a poetic foundation, into one of the strongest and most beautiful poems of Serbian love poetry, his late work and repentance, “Santa Maria della Salute.”

THE ORIGINS OF THE POEM

In the first half of 1909, Laza Kostić prepared his last book of poems in Sombor, which was published in Novi Sad by Matica srpska at the beginning of summer, on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of his literary work. At that time, his Julijana was incurably ill, and he, at the last minute, delayed the printing of the book, undecided whether to publish the poem that was just being created, and which he seems to have carried within himself unwritten for years, so that, maturing from parts of recorded dreams, it was finally sung in Sombor, between May 22 and June 2 (according to the old calendar), 1909.

Laza Kostić postponed the completion of his swan song, as he called it in the note about the dream recorded in the “Hungaria” hotel in Budapest on June 3, 1909 (Apotheose á Elle, Santa Maria della Salute, probablement mon chant de cugne, or Her apotheosis Santa Maria della Salute, probably my swan song), until the last moment.

As early as April 17, he wrote to the book editor Milan Savić from Sombor that he had one final poem in his head (in petto), a little long. He wrote to Savić again from Sombor on May 22 and asked him not to print the last sheet of the book before Pentecost because it might happen that he would still write the unsung poem with which he intended to finish the book. The day before leaving for Pešta and Vienna for Julijana’s treatment, on June 1, he wrote to Savić from Sombor that he would send the final poem from the road and that he had two or three more stanzas. On the same day, in a second letter, he announced that he hoped to be able to send his final verse creation as soon as he arrived in Pešta or, at the latest, upon arrival in Vienna, but he also clearly hesitated about that poem because he added in the same letter that, if he did not send the poem by June 9 at the latest, it meant that he had changed his mind (it is terrifying to imagine how impoverished Serbian lyric poetry would be if that had happened). Finally, on June 3, from the aforementioned Pešta hotel, he sent the poem to Milan Savić, with a short message: Here is my finale. Send the proofreading to me in Vienna.

Given the preserved original manuscript (autograph) of its larger part, the poem was created fragmentarily, and the final order of the stanzas did not also mean their chronological order of creation. The testimony of the preserved records of the verses of this poem, written with a plain pencil, testifies to Kostić’s mastery and unsurpassed feeling for beauty and style during minor corrections of the original forms of some words, thoughts, and verses. When all this is complemented by the preserved records from his “Dream Diary,” the revealed mystique of the creation of that ideal combination of harmony and beauty, a picture of miraculous poetic alchemy, perhaps unprecedented in the history of poetry, appears on the horizon (according to S. Vinaver, graphologists found traces of genius, intuition, dreams, mysticism, and mysterious features of ultimate aesthetic rapture in these Kostić manuscripts).

Unfortunately, Kostić’s record of the dream from June 3, 1909, in which he calls this poem his swan song, has not been preserved. The first preserved record of his dreams from that year was written 16 days later. The question remains whether Radivoj Simonović, who mentioned this June 3 record in his lecture in 1929, truly, as he said, burned some of the diary entries (Lest anyone should write a treatise about it—and although he clearly foresaw this, today the honourable doctor from Sombor would, undoubtedly, be horrified by the number of treatises written about Kostić’s remaining and preserved records from the “Dream Diary”). All this leads to the thought of what the appearance of the deceased Lenka in his dream on that crucial night, between June 2 and 3, might have been like, and whether she cut through all of Kostić’s dilemmas and hesitations regarding the publication of the poem that bore the name of the most beautiful Venetian baroque church.

“Santa Maria della Salute” represented the magnificent culmination of Kostić’s half-century of poetry and an immortal cosmic hymn in praise of the harmony of love and beauty, in which “it is as if all the energies of the language have been awakened to reach that high boundary of linguistic perfection beyond which, above the horizon of language, in silence, lies the world of essential poetry” (Lj. Simović).

The book was published in mid-July 1909. Mladen Leskovac describes the appearance of Kostić’s last book of poems as follows: “Upon returning from there (from Julijana’s treatment in Vienna), if not somewhat earlier, the book must have been ready. Julča certainly no longer had the strength to understand what was new, unusual, and extraordinary, stupendous, in that, mostly reprinted book. […] Just somehow when that book appeared, good Julča Palanačka died; Lenka Dunđerska, however, did not, completely and forever: from then on, she is immortal. The two of them, there, on the strict boundary of one death and one birth, are sharply separated, forever. Almost no one, not even Kostić’s friendly writers and critics (of whom, admittedly, there were not many at that time), noticed the last, long, previously unpublished poem with the unusual title – “Santa Maria della Salute” – in Matica’s jubilee collection of Kostić’s works. No one analyzed it, no one wrote reviews. Almost no one understood it either. Soon, in the whirlwind of events, both the poem and the poet’s collection were forgotten. Laza Kostić died only 17 months after the release of his last book of poems.

Tragic world upheavals soon followed, and his youthful political ideals were realized less than a decade after Kostić’s death; Serbdom and South Slavdom were liberated and united. In these turbulent historical events and changes, Serbian literature had almost died out. After the war, it was reborn, it broke new ground, rejected the old, and formerly recognized values were now being re-examined and often became the subject of ridicule or contempt. And then, in that breaking point, in the twenties and thirties of the 20th century, the prophetic words of the Czech writer and aesthetic Jiří Karásek, written about Laza Kostić, the magician of the Serbian language, in the 276th issue of the Annals of Matica srpska (1911), came true, when, only a few months after Kostić’s death, he boldly stated the almost heretical claim for that time that Kostić’s time was yet to come. He ended the article with the words: The prophet is a foreigner. But his words will be fulfilled. In those post-war years, Laza Kostić’s last poem was finally noticed, understood, and revealed in all its greatness and lavish linguistic beauty. The last, unnoticed cry of Serbian Romanticism thus became the first universally noticed roar of Serbian Modernism.

The new Serbian literary criticism and public understood how the old poet, reconciled with both heaven and earth towards the end of his life, with his final astral and spiritual poem (which is both a tragedy and a hymn, both a dithyramb and an elegy, both discord and reconciliation, both a spasm, and a tension, and a release) finally completed the weaving of that thin weave between reality and dream, with which he masterfully demarcated Serbian Romanticism and Modernism.

MORE TOPICS:

DODIK: BiH will not become a member of NATO, because Republika Srpska opposes it!

TODAY WE CELEBRATE SAINT ALIMPIUS: He stopped the plague and leprosy, avoid eating this today!

Source: Ravnoplov, Photo: Wikimedia Creative Commons