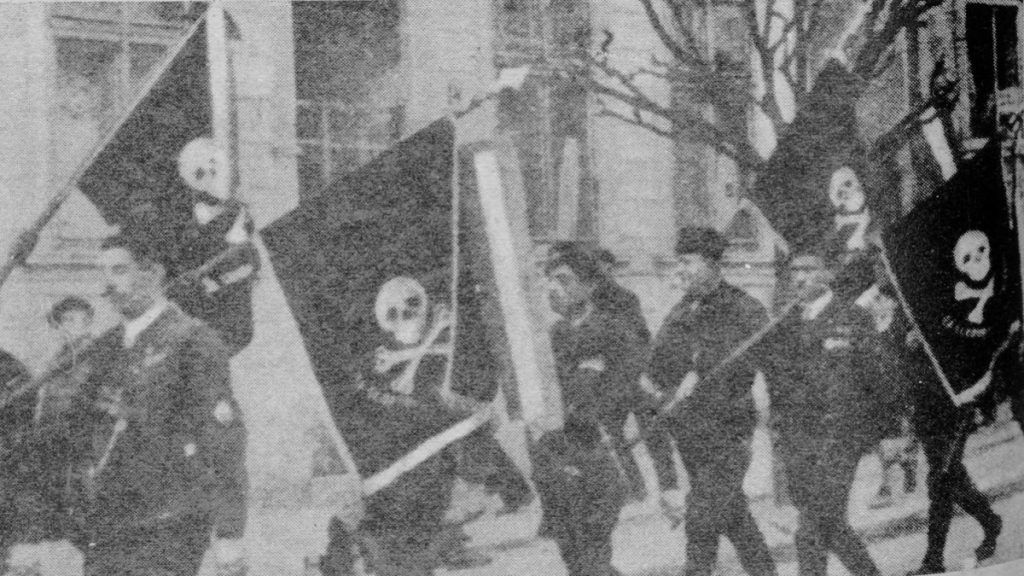

Oaths sworn on the cross, masked rituals, a constitution and a coat of arms featuring a hand holding a flag with a death’s head and bones, alongside a bomb, a dagger, and a vial of poison, are just some of the symbols, rites, and myths of one of the most powerful Serbian secret societies of the early 20th century.

“Unification or Death,” also known as the Black Hand, was a secret revolutionary organization composed of officers and former conspirators whose goal was the national liberation and unification of territories inhabited by Serbs.

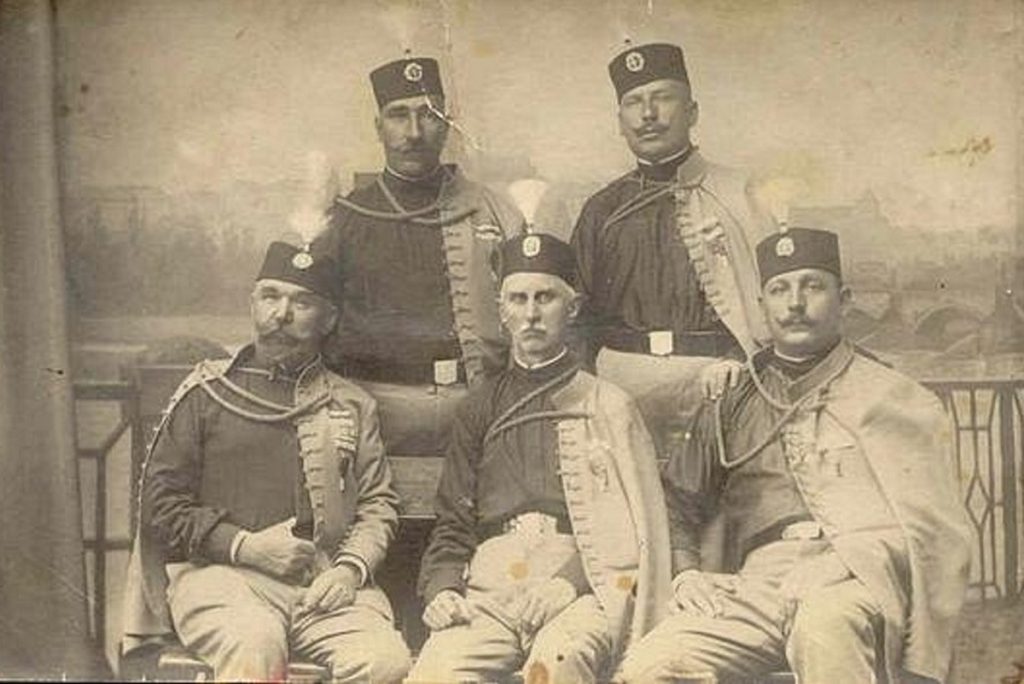

“A secret organization of people who were either Chetnik commanders or were connected to Serbian propaganda in the area of Old Serbia – territories that were still under the rule of the Ottoman Empire at that time,” Boris Marković, a historian and curator at the Historical Museum of Serbia in Belgrade, tells BBC Serbian.

The most prominent figure of the Black Hand was Dragutin Dimitrijević Apis – a colonel, a conspirator in the May Coup, the chief of intelligence, as well as an officer whom many in the army feared.

The beginning of the end for this secret organization began on April 2, 1917, with the Salonica Trial – a political trial of the Black Hand members that ended in June of the same year with the execution of three prominent members: Apis, Ljubomir Vulović, and Rade Malobabić.

They were rehabilitated only after World War II in socialist Yugoslavia – in June 1953.

What was the Black Hand?

The official name of the organization was “Unification or Death,” while the Black Hand was an Austrian name that became common among the inhabitants of Serbia.

It was formed in May 1911, at a time when secret societies and youth organizations were springing up across Europe.

Various stories and myths circulated about it, and even newspapers wrote about “masked rituals,” modeled after Masonic gatherings.

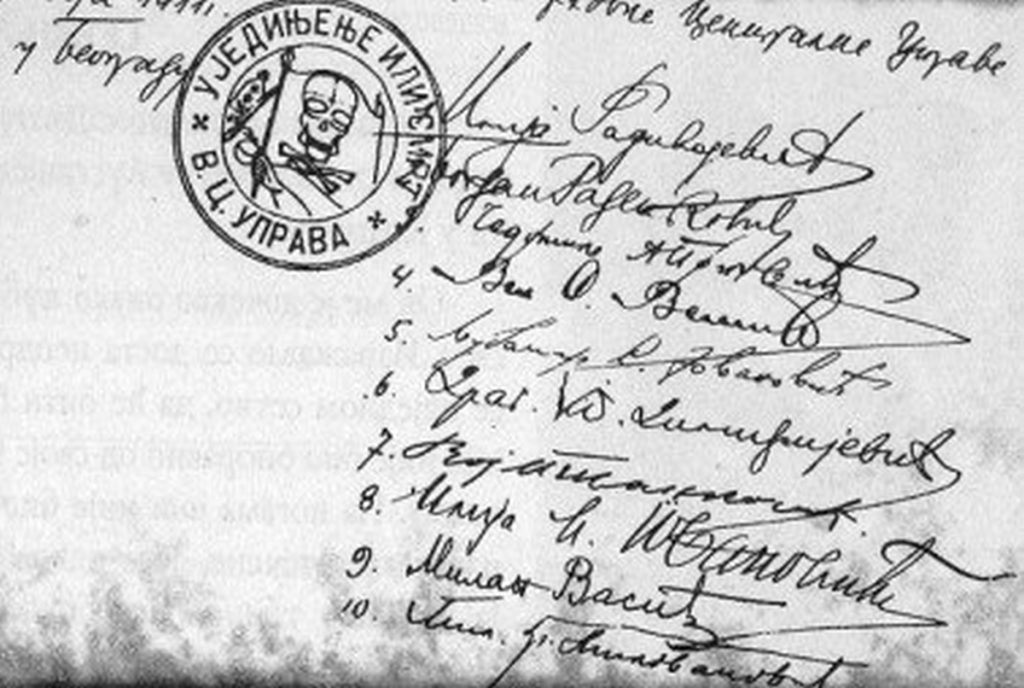

“Essentially, we don’t know much about it, but we know for sure that it had its own constitution and that an oath had to be taken upon joining the organization,” says historian Marković.

It was founded by Bogdan Radenković – a political representative of Serbs in the Ottoman Empire and a professor in Skopje.

He connected with members of the Serbian Chetnik Action – an armed formation that operated in the territory of so-called Old Serbia, which includes the regions of Raška (Sandžak), Kosovo, Metohija, and present-day North Macedonia, still part of the Ottoman Empire.

Among the Chetnik commanders were, among others, Velimir Vemić, Voja Tankosić, and Vojin Popović, better known as Duke Vuk.

Historian Marković says that armed members of this unit secretly went to areas inhabited by Serbian populations that were not yet liberated.

It turned out that in those areas, they also clashed with Bulgarian komitas, later the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization.

“It was a kind of struggle for propaganda and influence, that is, for the spread of either Serbian or Bulgarian national identity among the Slavic population in the area of present-day North Macedonia, as well as the protection of the people from Albanians and Turks,” explains Marković.

They were financed, he adds, by “certain circles of the Belgrade elite” – doctors, some politicians and diplomats, but not the state, at least officially.

The sole goal of this organization, says Marković, was the national liberation and unification of territories inhabited by Serbs, but unlike political parties, they believed “that this goal is achieved by weapons,” that is, by revolution.

The Black Hand was hierarchically structured and from the beginning rejected “democratic, political means for achieving goals.”

“They viewed politics as something dishonorable and said that ‘parties and party struggles pollute the pure fabric of Serbian society,’ and that political struggle itself is not a good way to fight for national goals,” the historian emphasizes.

Soon after its founding, they began publishing the newspaper Pijemont, whose editor was Ljubomir Jovanović Čupa.

There, says Marković, Prussian models can be observed, that is, their militarism which they saw as a “way out for the entire Serbian society.”

The organization spread rapidly, and one Black Hand member could bring in five new members.

There was a vow of silence, so newcomers swore that they “knew only him and no one else.”

From about a hundred members at the beginning, it is estimated that the organization eventually numbered between 1,000 and 2,000 people.

Their base was in the Belgrade garrison, but they were also scattered throughout the Ottoman Empire and Austria-Hungary.

The Black Hand Before its Founding – The May Coup

Although the founding of the Black Hand was not even planned at the time, some of its prominent members participated in the May Coup on the night between June 10 and 11, 1903 (May 28 and 29 according to the Julian calendar).

That night, a group of dissatisfied conspirators led by senior officers carried out a coup d’état and assassinated King Aleksandar Obrenović and Queen Draga Mašin.

Among the leaders of the coup that led to the end of the Obrenović dynasty were Jovan Atanacković, the former brother-in-law of Queen Draga – Aleksandar Mašin, as well as Petar Mišić, who years later would be on the commission that tried Apis and the Black Hand members in the Salonica Trial.

The palace gates were opened by another of their future enemies – Petar Živković.

He would later become the first man of the White Hand, an organization of officers who opposed the Black Hand and “wanted to create their own influence with Regent Aleksandar Karađorđević and the officers themselves,” explains Marković.

In addition to Apis, other Black Hand members such as Voja Tankosić, who commanded the firing squad for Queen Draga’s brothers, as well as Ljubomir Vulović, Čedomir Popović, and others participated in the coup.

The Balkan Wars and the Beginning of Conflict with Pašić

Until the beginning of World War I, there were three centers of influence in Serbia – the king, or regent, then the government, the assembly, and political parties, and finally the army and its officer structure, headed by Apis and the Black Hand, Marković points out.

The army at that time, the historian adds, represented the “pillar of the Serbian state,” the people trusted it, and it had “serious political influence.”

With the outbreak of the First Balkan War in October 1912, Chetnik formations, led by Black Hand members, “acted in accordance with state policy,” while after its end, in May 1913, the first serious conflict arose between Nikola Pašić, the radical prime minister, and Apis.

This war liberated Old Serbia.

Since Austria did not allow Serbia access to the Albanian coast, the Serbian army remained in Macedonia – a territory that was supposed to be divided with Bulgaria, which led to a sharp deterioration in relations.

Pašić wanted an agreement with the Bulgarians, but Apis and the officers, the liberators of that territory, did not want to leave it.

“In the summer of 1913, the Bulgarians attacked Serbia, which helped prevent an escalation of the conflict between Pašić and Apis because it provided an opportunity for both to gather their forces and resist the attack on the Bregalnica,” Marković states.

After the Second Balkan War, new problems arose because it was necessary to find a model for governing the new territories, inhabited by more than a million and a half people, among whom were not only Serbs.

“Pašić advocates for the democratic principle that elections be held there and a new government be formed.”

“On the other hand, Apis believes that for the next 10 years, only military administration must rule, which will lead to the integration of the local population into society at some point,” explains Marković.

The government then adopted the so-called “regulation on priority,” according to which civilian authority in the conquered territories had precedence over military authority.

However, Apis begins to pressure King Peter Karađorđević to overthrow Pašić’s government.

“King Peter did that, which was not seen as a legitimate act because that government had a majority in parliament.”

“In those circumstances, he was criticized by the allies – representatives of Russia and France,” adds Marković.

Through their intervention, Pašić returns to the head of the government, King Peter withdraws from the political scene, while Apis still has enormous influence.

Regent Aleksandar Karađorđević, who supported the Black Hand and on one occasion even financially helped them with 26,000 dinars at the time, came to the king’s place.

This was just a few days before the assassination in Sarajevo of Austro-Hungarian Crown Prince Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie on June 28, 1914, which was the immediate cause of the outbreak of World War I.

It was organized by Young Bosnia, and its member Gavrilo Princip fired the shots.

World War I and the Black Hand

Apis entered World War I as the chief of Serbian intelligence, the head of the Intelligence Department of the Supreme General Staff.

His agents were throughout the country, even in the two neighboring monarchies – Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire.

“If it weren’t for the Black Hand, the then Serbian military intelligence service would not have had serious information from abroad,” says historian Marković.

However, the war brought many challenges, and at the end of 1915, a new conflict arose between Apis and Pašić.

At a time when Austria-Hungary and Germany were planning an offensive against Serbia, fears arose that Bulgaria, if it joined the Central Powers, would close the Serbian army’s retreat route through the Morava-Vardar valley towards Thessaloniki.

Serbia’s preemptive attack, says Marković, was called off by the Allies, who hoped that Bulgaria would still join the Entente – the military alliance of Great Britain, France, and Russia.

“Apis has no dilemma that Pašić, as a negotiator with the allies, must have, and believes that the Bulgarians must be dealt with as soon as possible in order to secure the direction towards Thessaloniki.”

“The wishes of the Serbian officers were not granted because the allies did not allow it, and the Serbian army reached Corfu via the more difficult route through Albania, and then after recovery, to Thessaloniki,” the historian adds.

In the atmosphere of defeat, the government and the army began to shift blame onto each other, and the further development of the conflict was prevented by the difficult circumstances they found themselves in.

Many prominent members of the Black Hand perished on the front lines in the first two years of the war.

Voja Tankosić died from wounds sustained during the Serbian army’s retreat in the autumn of 1915, while Vojin Popović – Duke Vuk – was killed in 1916 at Kajmakčalan.

In this way, Apis lost trusted people who “had his back” in “any conflict with Pašić and the regent.”

Thus, an opportunity arose, says Marković, for the two centers of power – the king and the radical government, with the help of the White Hand, to unite in an effort to defeat the Black Hand.

“They used the incident of September 11, 1916, when someone near the village of Ostrovo, not far from Thessaloniki, shot at the car in which Regent Aleksandar was.”

Apis was arrested on December 27th, followed by dozens of other Black Hand members.

After several months of preliminary investigation, the Salonica Trial began on April 2, 1917.

The organizers of the trial initially had the idea of passing a law on the “Extraordinary Military Court for Officers” because the existing one applied to non-commissioned officers and soldiers, which the Government opposed.

“Violence Against Justice”

After several changes to the indictments, Apis and the accused members of the Black Hand were ultimately tried for the assassination attempt on the heir apparent and belonging to a subversive organization, that is, treason.

“In Thessaloniki, it was a political trial par excellence, violence against justice.”

“Slobodan Jovanović, an excellent connoisseur of the law at the time, who knew them personally – if nothing else, he was familiar with their way of thinking – certainly assessed it as such,” Mile Bjelajac, director of the Institute for Contemporary History of Serbia, tells BBC Serbian.

The only witness in the proceedings was a certain Temeljko Veljanović, previously sentenced to death for murder.

He said that he saw Rade Malobabić, Apis’s agent and a Black Hand member, shooting at the car in which Regent Aleksandar was.

With this testimony, Temeljko’s sentence was supposed to be commuted to life imprisonment.

“At one point in the investigation, almost everything fell apart on a simple question prepared for the witness as to whether the car was going from Lake Ostrovo towards Thessaloniki or vice versa.”

“Who can forget that if they were an eyewitness at the scene? He got confused, they somehow covered it up,” says Bjelajac.

The Sarajevo Assassination

In the preliminary investigation, Apis took responsibility for the Sarajevo assassination, stating that Rade Malobabić organized the action on his orders.

“We have fairly clear testimonies from people who belonged to the Black Hand, and even from Apis himself, that he was in some way connected to Young Bosnia and that through Rade Malobabić he organized actions in accordance with the actions of the Black Hand,” states Marković.

Apis’s closest associate, Voja Tankosić, supplied the Young Bosnians with weapons from Chetnik warehouses in Serbia.

However, he did not provide the weapons for the Sarajevo assassination, Marković claims.

Although they were very close, he adds that these two revolutionary organizations operated separately.

Bjelajac believes that Apis took responsibility for the Sarajevo assassination because he did not want to allow “the radicals to kill Rade Malobabić,” his chief intelligence officer in Austria-Hungary.

Tankosić then informed Apis that there were “some children who would try something,” which is why he sought his consent “to let them.”

Without immediately considering the consequences, he gave him permission, but soon changed his mind and in several ways tried to prevent the assassination.

“If Apis had organized it, he would not have sent someone who doesn’t know how to shoot and who is throwing a bomb for the first time in his life, but he would have sent Bosnian komitas who had thrown hundreds of bombs and shot countless times,” says Bjelajac.

Marković believes that he did not do this to acquit Malobabić but to make it harder for Regent Aleksandar and Pašić to convict him in the eyes of the Serbian public with that confession.

However, this confession was not even discussed in court.

Marković says that the crackdown on the Black Hand members took place in parallel with the negotiations between the Entente and Austria-Hungary on a separate peace in 1916 and 1917.

“As one of the conditions for Austria-Hungary’s exit from the war, it is mentioned that the Austro-Hungarians want all those people they believe were involved in the Sarajevo assassination to be removed.”

“That also applied to Apis, it was a good moment to exploit international pressure to achieve his own political gain,” Marković believes.

Bjelajac claims that the Serbian government learned about the secret negotiations between France and Austria-Hungary only in the spring of 1918, when the new French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau presented the content of the Austro-Hungarian proposals in the assembly.

“Those negotiations failed before the end of the Salonica Trial,” says Bjelajac.

After World War I, “certain witnesses” also spoke about how “President Clemenceau” sought “Apis’s head” in order to allegedly “accommodate Austria-Hungary.”

That, the historian adds, is a “false claim” because during the Salonica Trial he was just an ordinary member of the French parliament.

“With these voices, the perpetrators of the trial, that is, those who were in a position to pardon the convicts, certainly freed themselves of at least part of the guilt,” writes Bjelajac in the foreword to the book Colonel Apis, by his nephew Milan Ž. Jovanović.

He also points out that during the trial, “France, Britain, and democratic Russia” intervened against the trial, and especially against the execution of “drastic punishments.”

What Happened to Apis and the Black Hand?

The trial lasted until the beginning of June 1917.

Dragutin Dimitrijević Apis, Ljubomir Vulović, and Rade Malobabić were sentenced to death.

They were shot at dawn on June 26th in Mikri, near Thessaloniki.

“Before their death, the verdict was read to them for hours while they were tied to a tree, with blindfolds over their eyes,” adds Marković.

Six other Black Hand members were sentenced to death but were subsequently pardoned.

They financially assisted the widow of Major Ljubomir Bulović while they were free.

The founder of the Black Hand – Bogdan Radenković – died in a prison hospital on June 30, 1917.

“Judicial Murder Without Basis in Law”

Bjelajac says that Professor Slobodan Jovanović as early as 1919, at the invitation of Regent Aleksandar, expressed doubts about the legality of the trial.

“Jovanović explained that the death penalty could not be based on the law and that it was a judicial murder,” the historian wrote.

“For proven guilt, Serbian law required the confession of the accused or at least two witnesses. That was not the case.”

“Even the only witness does not testify about him but about Malobabić.”

“He was convicted on the basis of ‘circumstantial evidence,’ but such evidence only leads to a lighter sentence and certainly not the most severe,” writes Bjelajac.

Karađorđević replied that “his people did not present it to him that way.”

“To pardon an officer who tries to kill his Supreme Commander in the middle of a war would mean completely destroying military discipline,” the regent justified himself.

Legacy and Rehabilitation

After the Salonica Trial, the Black Hand officially ceased to exist, but its spirit lingered.

Some of its members, such as Mustafa Golubić and Božin Simić, continued their political engagement as communists in the Soviet Union.

Marković says that Simić came to Yugoslavia before the military coup on March 27, 1941, and managed to convince the president of the putschist government, Dušan Simović, and their representatives that the Soviet Union would stand behind Yugoslavia.

PRATITE NAS I NA INSTAGRAMU:

MORE TOPICS:

SERIOUS INCIDENT IN BELGRADE: Part of the ceiling collapsed in KBC Bežanijska kosa, a nurse injured!

Source: BBC

Foto: Wikimedia Creative Commons