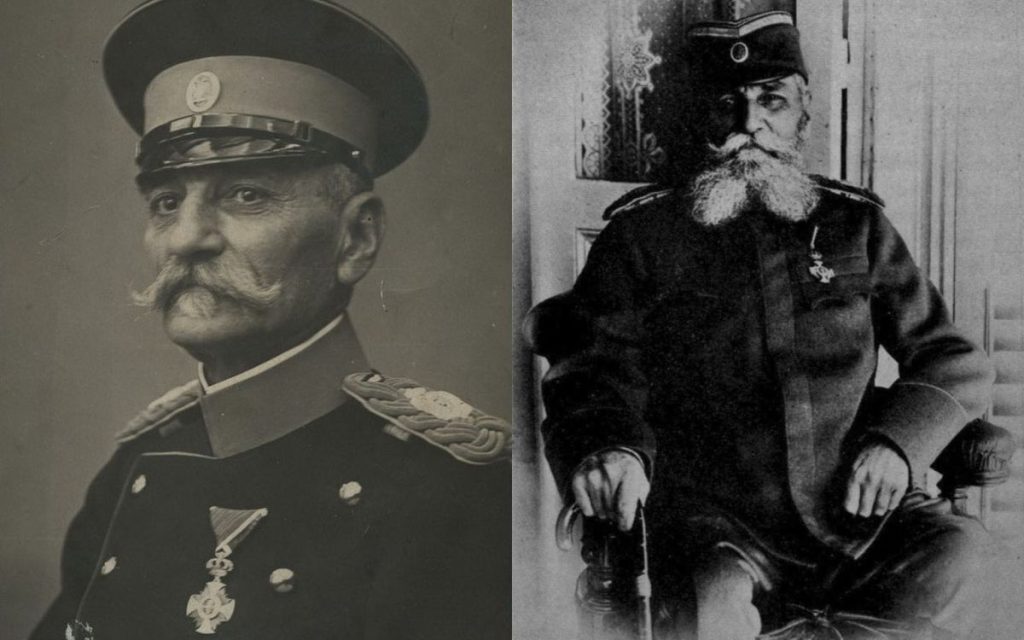

With a neatly combed mustache and a discreet grizzled beard, a gaze bordering on worried, clad in a red uniform adorned with sparkling orders and medals. This is how painter Uroš Predić, in one of the most famous portraits from his rich artistic oeuvre, depicted Peter I Karađorđević, arguably the most beloved monarch among Serbs.

“He is a king remembered as good, but when you look closely, he was a politically unfounded and un-initiative figure,” says Nebojša Damnjanović, retired curator-advisor of the Historical Museum of Serbia, for BBC in Serbian.

Karađorđe’s grandson was elected King of Serbia in 1903, a few days after the coup d’état that extinguished the Obrenović dynasty, and after almost half a century spent outside his homeland. During his reign, Serbia experienced economic growth and democratic development, and he was remembered as an honest ruler who was not an absolutist, unlike his predecessors from the Obrenović dynasty, Damnjanović points out.

“Uncle Pera,” as the people affectionately called him, earned his place as the most popular Serbian monarch, among other things, through victories in the Balkan Wars and World War I, after which a large state was formed—the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, later Yugoslavia.

The Old King’s Carefree Childhood in Turbulent Times

The Principality of Serbia, where Peter grew up, was torn between two ruling families—the Obrenovićs and the Karađorđevićs—and also two cities—Belgrade and Ottoman Istanbul, to which Serbian vassal princes still paid tribute.

Peter was born in Belgrade on July 11, 1844, as the fifth child in the family, during his father’s reign, Prince Aleksandar Karađorđević. During Peter’s upbringing, Belgrade had around 25,000 inhabitants, which, Damnjanović emphasizes, ranked it among the small cities by Balkan standards. He adds that half of the city’s population was still Muslim, and the Ottomans still held the Belgrade Fortress on Kalemegdan.

In such circumstances, amidst the political turmoil between the Karađorđevićs and Obrenovićs that marked society at the time, Peter completed primary and high school in Belgrade. Historians describe him as a perfectly ordinary boy who socialized with his peers. The only difference was that he lived in a court that, at the time, did not meet the basic criteria to be called such.

“My professor and colleague Dragoljub Živojinović, in his multi-volume book on King Peter, says that Peter grew up like any boy from a wealthier Belgrade or Serbian family,” Damnjanović states.

He says that his mother, Persida, an authoritarian and enterprising woman from the famous old and respected Nenadović family of Valjevo, played a significant role in his upbringing. In contrast, Peter’s father and Karađorđe’s son, Aleksandar, was, according to testimonies, insecure and weak, so the family’s position was not firm and secure.

He was brought to power by the so-called Constitutionalists after Vučić’s Uprising in 1842—a revolt led by Toma Vučić Perišić, an influential military leader from the First and Second Serbian Uprisings, after which the then-head of state, Prince Mihailo, Miloš Obrenović’s son, was forced to leave Serbia. Gospodar Vučić, as he was known among the people, belonged to the Constitutionalists—a group of prominent people, bureaucrats, and merchants who opposed the autocratic rule of Mihailo’s father, Prince Miloš, and desired the rule of law.

The Constitutionalist regime had a strong police force and an elaborate espionage apparatus, Damnjanović claims. He adds that they invested heavily in monitoring and controlling the people to avoid a scenario by which they themselves had seized power.

Fate, however, played a similar trick on them and Prince Aleksandar Karađorđević in 1858, when after the Saint Andrew’s Assembly, which legalized the institution of the national assembly and laid the foundation for the representative system in Serbia, the Constitutionalist regime ended, and Peter’s father was overthrown. Prince Miloš Obrenović, the founder of their dynasty which would rule Serbia for the next almost half a century, came to power for the second time, precisely the amount of time Peter would spend in exile. The Karađorđevićs then moved to an estate near Arad, then a city in the Austrian Empire—the successor state to the Habsburg Monarchy and predecessor of Austria-Hungary, and today in Romania.

Youthful Days in Geneva and Paris

Immediately before his father’s overthrow, the fourteen-year-old Prince Peter was sent for further education to the Venel-Olivier institute in the Swiss city of Geneva. There, he learned that his family had been expelled from Serbia, which made him bitter and sad, and he spent most of his time alone, Damnjanović recounts.

After completing his education, he moved to Paris, where in 1861 he enrolled in Collège Sainte-Barbe, and a year later, the then-famous military academy in Saint-Cyr. Although literature and the press often state that he graduated from the military academy, Damnjanović claims this is not true.

“He studied something there, started, but did not reach the final exam and obtain a rank; he remained in the first or second year. If you look at the years, you see that military academy education couldn’t fit into that time,” Damnjanović emphasizes.

Karađorđević remained in Paris where, the historian says, he led a “worldly life.” “He was a young prince who enjoyed life, played cards, caroused, read a bit…” His brief episode of engaging in painting and photography began on the heels of this youthful enthusiasm.

Besides entertainment and hedonism, he also managed to politically define himself, embracing the ideas of “liberalism, parliamentarism, and democracy.” Thus, in 1868, he translated John Stuart Mill’s essay On Liberty, which would later become his political program.

“One should not take his political views from that period too seriously; after all, he was a claimant prince who looked both left and right. He certainly was influenced by those ideas, but on the other hand, he was also quite a militant type, which does not align with liberalism,” Damnjanović points out. He also doubts that King Peter translated this work himself. “In his long life, he never translated or published anything else, which was also the case with photography and painting. Obviously, he was helped at the time; people around him advised him that it would be useful to recommend himself to the people in that way,” the historian believes.

While living in Paris, he occasionally visited his parents in Banat, with whom, Damnjanović claims, he was not on good terms. The reason was his rapid expenditure of his inheritance. Although various legends circulated, for example, that he was transported back to his homeland in a barrel, he crossed the border into Serbia only once, at the Danube, in the east of the country, where he stayed for a very short time.

French Foreign Legion and Petar Mrkonjić

He joined the French Foreign Legion—an elite unit of the French army composed of volunteers from other countries—in 1870 and participated in the Franco-Prussian War that same year. Damnjanović believes that the reasons for Peter’s joining the Foreign Legion and participating in the war should be sought in his youthful adventurous spirit, as well as his desire to repay the country that welcomed him.

However, France lost the war, and the future Serbian king did not achieve any significant results in battle. “There are testimonies that he was captured in conflicts, a German officer then beat him, and he found salvation in the middle of winter by swimming across a river,” claims the retired curator. Peter then left the war and the French army. The historian claims that after some time, he sought a certificate of participation, which led to a warning not to do so, as he could be tried as a deserter.

He continued writing the pages of his war diary in Bosnia and Herzegovina. There, in 1875, the so-called Nevesinje Rifle—an uprising of Serbs against the Ottomans in Herzegovina that soon spread to Bosnia—erupted. Karađorđević participated in this rebellion under the pseudonym Petar Mrkonjić. He, Damnjanović says, encamped in the Bosanska Krajina, in the east of the country, where he gathered a company and carried out “isolated, but limited, frustrated, and not very successful actions.”

“‘As long as I can pay for their rakija, they are with me; as soon as I don’t have money to pay for them to drink, they immediately go their separate ways,’ Peter says in his notes about the Serbs who joined him,” the historian quotes him. Although this action was also unsuccessful, the historian says it showed that the future King of Serbia harbored patriotic feelings and worked for the Serbian, as well as the family cause. “If nothing else, at least he went to that Bosnia, which was still Ottoman, and showed some courage; that cannot be denied.” Serbia secretly supported the rebels, but the Obrenovićs were more concerned about whether any of the Karađorđevićs would gain prominence there than about the outcome of the rebellion, Damnjanović points out.

Marriage, Diplomatic, and Political Connections

At the Congress of Berlin in 1878, Serbia gained independence, and four years later, it became a kingdom. At this pivotal gathering of representatives from a dozen states, the great powers made peace, relations in the Balkans were defined, and Serbia, in addition to formal independence, also received the Niš, Leskovac, Pirot, and Vranje districts. By decision of the National Assembly on March 6, 1882, a law was passed declaring the Principality of Serbia a Kingdom, while Milan Obrenović became the head of the monarchy.

King Milan pursued an Austro-philistine policy and alienated Russia. Therefore, according to historical testimonies, at Russia’s initiative, Petar Karađorđević was found, and at the urging of Petrograd (today’s Saint Petersburg), he was given the hand of Princess Zorka, daughter of the Montenegrin ruler Nikola I Petrović Njegoš. They married in Cetinje in the summer of 1883, but Zorka died after only seven years of marriage. Peter moved to Geneva with his sons Aleksandar and Đorđe and daughter Jelena. Previously, due to a poor financial situation, he sold his house in Paris in 1894. In Switzerland, Damnjanović says, they lived modestly, and relatives also came to their aid.

Peter continued to maintain ties with Russia. He visited in 1897 when he was received by Emperor Nicholas II. “To official Russia and their policy, the Karađorđevićs were a card against the Obrenovićs; that’s why Peter and his children were received there for schooling,” Damnjanović points out.

Peter also came into contact with the leadership of Nikola Pašić’s People’s Radical Party, whose leaders, after the Timok Rebellion in 1883—a popular uprising in eastern Serbia against government levies—were mostly in exile in neighboring countries. “Both were tied to Russia, which is logical because they had a common adversary—King Milan Obrenović,” Damnjanović explains. Upon Aleksandar Obrenović’s ascension to the Serbian throne, Peter tried to discuss with him the recognition of his princely title and the return of confiscated property, but without success.

A Return Paved with Blood and a Crown on His Head

Petar Karađorđević returned to Serbia in 1903 after the May Coup—a bloody coup d’état in which a group of disgruntled officers killed King Aleksandar and Queen Draga Obrenović. Among the prominent conspirators were important members of the secret revolutionary organization Black Hand, which would emerge a few years later and significantly influence state policy.

Damnjanović says there is no evidence that Peter was “to a greater extent” involved in the conspiracy. “He knew something through his people, but little depended on him,” he adds. The National Assembly elected him King of Serbia on June 15. Peter’s predecessor, Aleksandar Obrenović, was not elected king in this way, while the first monarch and Aleksandar’s father, Milan Obrenović, was. This extraordinary procedure for King Peter had to be followed because his family did not have a right to succession until then, Damnjanović explains.

The army was everywhere that day. “Sympathizers say the army maintained order, but an assembly surrounded by the army—that can be interpreted in various ways. Be that as it may, the army acclaimed him, the assembly elected him,” the historian says.

Peter I Karađorđević was crowned on September 21, 1904, one hundred years after the First Serbian Uprising, which his grandfather Karađorđe led against the Ottomans. This was the only coronation of a Serbian ruler in the 19th and 20th centuries, Damnjanović says. For this occasion, a crown was made from the bronze remnants of Karađorđe’s cannon. “Europe did not respond; only Montenegro came from the outside world because the impression of the 1903 massacre was very vivid,” the historian adds.

The Reign of King Peter

King Peter, according to historical testimonies, was a beloved Serbian monarch. Damnjanović says that from King Peter’s reign, the general judgment is that he was a positive figure who did not interfere, did nothing wrong, and did not strive for autocracy. Many historians agree that he strived to revive parliamentarism and democracy, advocated for a constitutional arrangement of the country, and was a proponent of liberal policy. He also enabled the entry of foreign capital into Serbia, the development of industry, crafts, and trade, as well as the opening of the University of Belgrade.

However, in some critical situations, such as the Annexation Crisis of 1908, when Austria-Hungary annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina, his reaction was absent. “He was a figurehead and was content with that, and political factors were very pleased about it, but in critical moments, many expected a little more initiative, which was not there because he was not capable of it,” Damnjanović believes. Nevertheless, he remained fondly remembered because he caused no harm, he adds. Because of this, along with the nicknames The Liberator and the Old King, he was affectionately known as Uncle Pera by the people.

“When, as a monarch, and he never behaved as such, he disputed with a citizen over the ownership of a plot of land and, after losing the dispute, he requested that the judge who made such a verdict be promoted,” historian Igor Micov told Glas javnosti.

After 11 years of reign—on June 24, 1914—King Peter transferred royal powers to his son, Crown Prince Aleksandar. This decision was preceded by a conflict between officers of Dragutin Dimitrijević Apis, the most famous member of the Black Hand, and Prime Minister Nikola Pašić. Apis demanded that the king dismiss the Radical leader, which he did. However, Pašić had stronger diplomatic ties than the king himself, so with the intervention of France and Russia, he was reinstated as prime minister. Peter withdrew in favor of Regent Aleksandar, due to an alleged illness. He formally remained the Serbian king until his death, but his son essentially governed the state.

King Peter’s Four Oxen

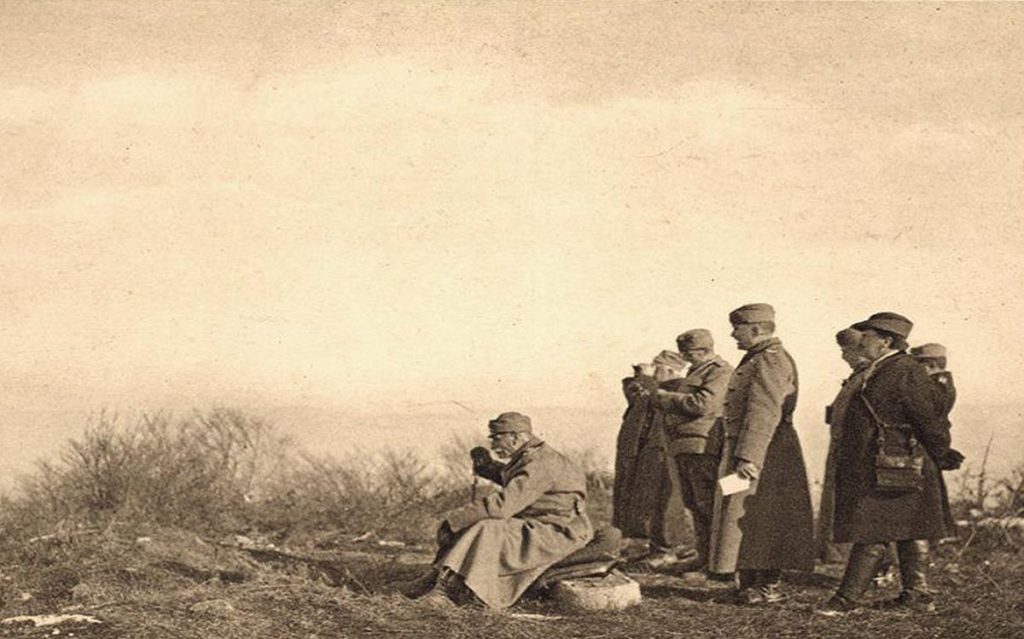

News of the outbreak of World War I in the summer of 1914 found him in Vranjska Banja. Since he was already seventy years old, the vojvodas (military commanders) and his son led all operations. After the victories in the battles of Cer and Kolubara against the Austro-Hungarian army, in the autumn of 1915, enemy forces tightened their encirclement around Serbia. Soldiers, civilians, and the state apparatus began their retreat across Albania. King Peter also trudged through the Albanian barren lands, and after the ordeal, he went to the vicinity of Thessaloniki, where he remained until the end of the war in 1918.

On December 1 of that year, a new state was formed—the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, and formally its first king was Peter I Karađorđević. The Old King lived only three more years after the Great War. He died exactly a century ago—on August 16, 1921—and was buried a few days later in his endowment on Oplenac, a hill near Topola.

Remembering Uncle Pera

The memory of King Peter lives on in Serbia today in the names of streets, squares, schools, stadiums… His significance, even today, a hundred years after his death, does not wane because many consider him an extremely important figure in Serbian history, which, Damnjanović says, does not have the continuity from the Middle Ages like other great European nations.

“The people and states try to find some anchor points, and Peter is part of that, unblemished by anything ugly.”

Mrkonjić Grad in Republika Srpska (Bosnia and Herzegovina) and Petrovac na Moru in Montenegro are named after him. Zrenjanin was called Petrovgrad before World War II, and his monument still stands in the central city square. In Paris, an avenue is named after him, and there is a joint monument with his son Aleksandar.

MORE TOPICS:

VUČIĆ ON STUDENTS: “Times come when all the social dregs, the sludge, all the worst in a society surfaces”

TEXAS ON EDGE: These are the Girls Missing from the Camp During Floods, Search Continues! (PHOTOS)

Source: BBC Foto: Wikimedia Creative Commons