“I suffered greatly and was greatly tormented. But I forgive everything—I forget everything. What pains me is only that I was removed from the position of Chief of Staff of the Supreme Command in such a way, as I would not have sent even my worst orderly back to headquarters.”

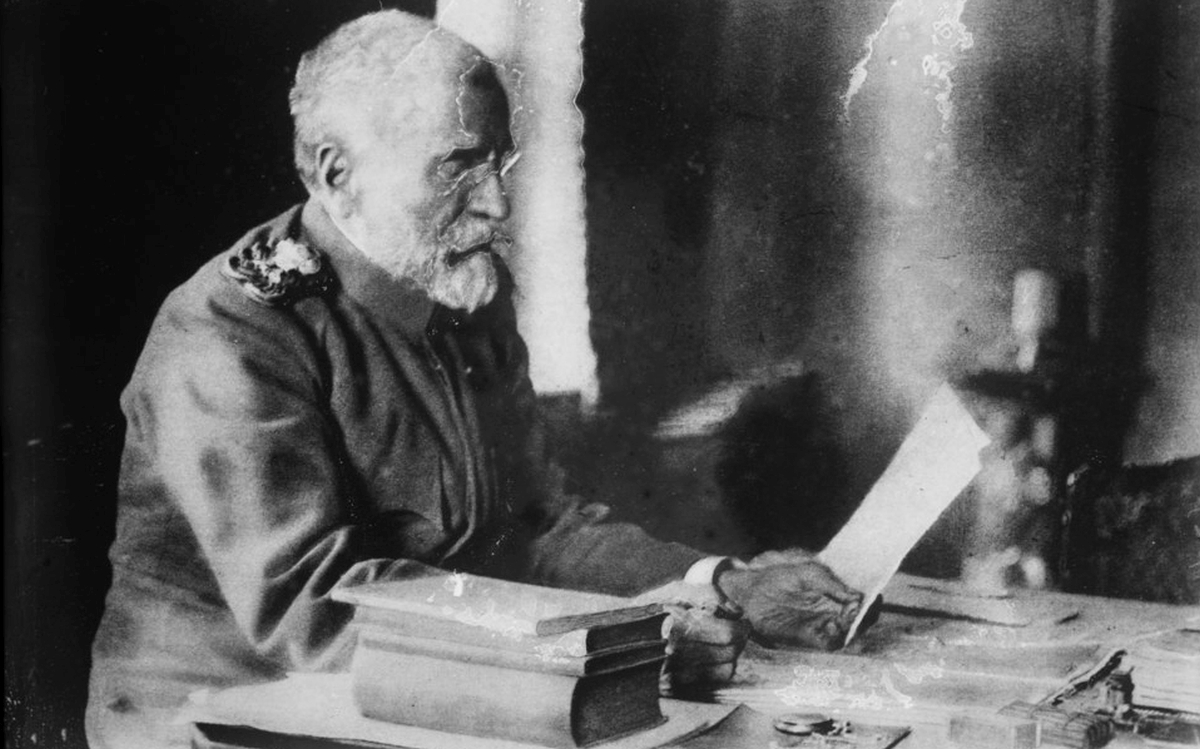

On this day in 1847, Radomir Putnik was born, a great military commander and strategist, Chief of Staff of the Supreme Command (1912–1916), credited with Serbian victories in the Balkan Wars. He successfully organized the defense of Serbia in 1914, and after the collapse of his army in the winter of 1915, he was dismissed due to illness. He died while receiving treatment in Nice in 1917.

Radomir Putnik was born in Kragujevac to his father Dimitrije, a teacher, and his mother Marija, to whom he was attached until the end of her life and who had a much stronger influence on him than his father.

The surname Putnik originated when the duke’s grandfather Arsenije moved from Kosovo to Bela Crkva in Banat. When asked his name, the then seven-year-old Arsenije replied that he was a “traveler in an unknown direction,” and so he was called Putnik.

Radomir Putnik completed elementary and secondary school in Kragujevac. He was a good student, but despite being measured and polite, he liked to impose himself in society as the first and to have his word listened to.

He did not like large company and chose modest people as friends—those who listened to him as a leader. Throughout his life he was modest and did not boast about his successes.

The military calling

He spoke German fluently, played the guitar and sang when his parents asked him to. A decisive influence on his choice of a military career was Duke Stevan Knićanin.

After completing high school, he enrolled in the Military Academy in Belgrade in 1861, graduating in 1866 as eighth in his class. He excelled in knowledge of military tactics, strategy, geography, weapons and artillery, and was also an excellent draftsman, while his great passions were horseback riding and gymnastics.

He experienced his first wartime experience as a captain of the second class in 1876 during the First Serbian–Turkish War. His wartime path began with a defeat in the Battle of Kalipolje, with heavy losses, but that defeat was a lesson he never forgot.

At the battle near the village of Adrovac, when the situation seemed hopeless, Putnik appeared at the head of a battalion with a drawn saber, thus raising the soldiers’ morale, after which the Serbian army launched a counterattack and repelled the enemy.

The future duke then clashed with senior officers and sided with his soldiers, a trait he retained until the end of his career.

Loyal, but sincere

Having proven himself a capable and brave officer and an excellent commander with great creative initiative, Putnik was quickly promoted to the rank of major.

In the Second Serbian–Turkish War, which began at the end of 1877, Putnik commanded the Rudnik Brigade of the first class and made a significant contribution to the liberation of Niš. His brigade also participated in the liberation of Grdelica and Vranje, and then pursued the Turks toward Bujanovac, where it ended its campaign due to exhaustion. Putnik’s army then advanced to Gračanica and Lipljan.

In the Serbian–Bulgarian War, which broke out in 1885, as an artillery lieutenant colonel he commanded the Danube Division and suffered defeat.

After that war, a reorganization of the neglected intelligence service was carried out, and that task was entrusted to Putnik, who sought for operational data to serve the General Staff rather than be used in political reckonings.

When King Milan Obrenović abdicated the throne in favor of his son Aleksandar Obrenović and the constitution was changed, democratic currents swept through all segments of Serbian society, including the army.

Putnik was loyal to the crown, but he never knew how to ingratiate himself with kings—neither Milan nor Aleksandar—and he was repelled by those who did. Both kings considered such conduct anti-dynastic, as they were accustomed to officers behaving submissively before them.

Unfit

For that reason, in 1893 he was dismissed from the position of Assistant Chief of the Main General Staff and appointed head of the examination commission for the rank of major, which was a clear sign of disfavor.

He was retired in October 1896, and former King Milan claimed that Putnik was retired because of participation in a conspiracy against King Aleksandar.

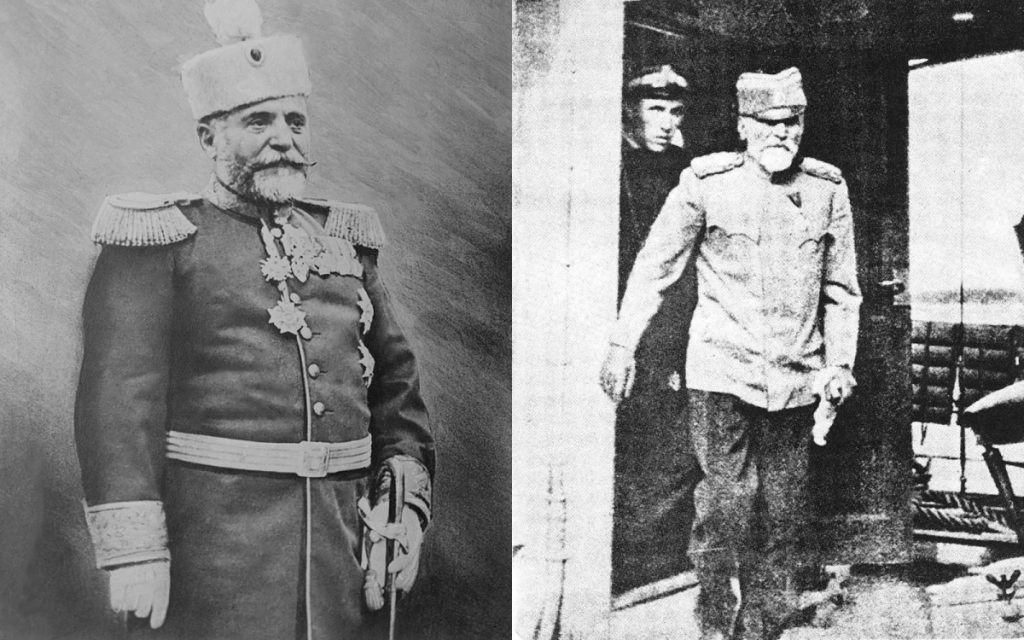

After the assassination of King Aleksandar, Putnik was returned to military service three days after the enthronement of King Peter Karađorđević, with the rank of general, and was appointed Chief of the Main General Staff, a position he continuously held for twelve and a half years.

The Balkan Wars

In the First Balkan War (1912–1913), Putnik advocated the creation of an alliance of Balkan Christian states directed against Turkey. He assumed that Turkish forces would be positioned around Ovče Polje. He misjudged this, which prevented the realization of his idea to assemble the forces of three armies that would deliver a final blow to the Turks.

Military experts, however, believe that Putnik essentially assessed the situation well, and that he created from the First Army, which moved along the Morava–Vardar axis, a very strong and disciplined force capable of defeating the Turkish Vardar Army regardless of its position. Confirmation of the experts’ reasoning was proven by the Battle of Kumanovo, in which the Serbian army won.

Putnik inflicted the final defeat on the Vardar Army at the Battle of Bitola, where he tactically sent the main body of forces via Veles and secondary forces via Kičevo toward Resen, thereby completely surprising the Turkish command.

Before the Second Balkan War (1913), at the government’s request, Putnik committed himself to doing nothing that would give Bulgaria a reason to declare war.

By this he renounced any strategic-operational initiative. Despite this, he assessed the situation well and halted Bulgarian attacks from multiple directions (the Bregalnica, Krivoreč, Sofia–Nišava, and Timok–Danube directions) and organized a counteroffensive in cooperation with Serbian allies in the Second Balkan War. The outcome of this operation was victory in the Battle of Bregalnica and Bulgaria’s capitulation.

World War I

After the end of the two Balkan Wars and the Albanian uprising, the number of fallen Serbian soldiers rose to 37,500, and Serbia was gripped by major internal problems.

After the assassination of Austro-Hungarian heir Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo, an Austrian attack was expected as early as July 25, when the mobilization decree was issued.

The response of military conscripts was high, as patriotic sentiment among the people was at its peak following victories in previous wars. Mobilization of combatant and non-combatant personnel was completed in 12 days, with 450,000 men mobilized.

Putnik was undergoing treatment at the Austrian spa of Gleichenberg and was ordered to return to Serbia.

Preparations for the defense of the country were carried out according to his plans, in whose development Duke Putnik cooperated with his deputy, General Živojin Mišić.

The Battle of Cer was potentially won on the very first day thanks to Putnik’s decision to timely transfer reserve forces to the most threatened sectors of the front and to close the axis between Šabac and Valjevo.

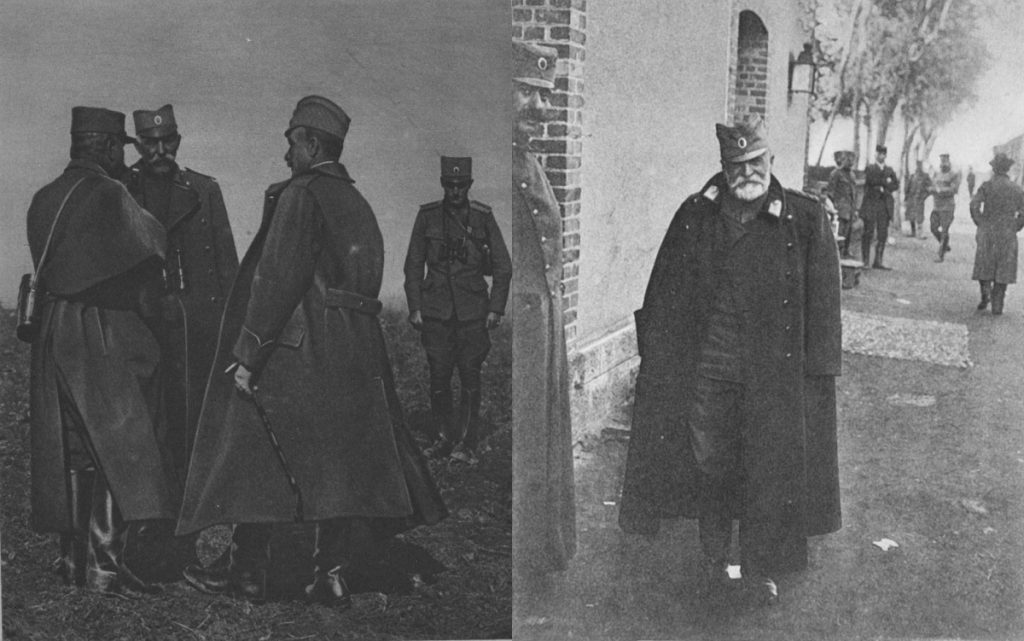

Historians believe that Duke Putnik, although ill, showed great composure, boldness, and flexibility during the conduct of operations. Some reproach him for not transferring units from the northern front more quickly, but he lacked information about the movements of Austro-Hungarian troops in those positions.

Duke Putnik’s contribution to the first Allied victory is immeasurable. In this battle, the Serbian army won thanks to his timely adaptation to the situation.

The Battle of Mačkov Kamen, in which the Serbian army was defeated, was until then the most massive engagement on the Serbian front.

The defeat of the Serbian army was not caused by Putnik’s orders, but by the technical superiority of the Austro-Hungarian army, poor intelligence work by the Serbian service, as well as a lack of equipment for mountain warfare and ammunition of all calibers. Only during these battles did it become clear how right Putnik had been when he advocated the procurement of mountain guns even before the Balkan Wars. A factor that significantly influenced the course of the battle was also that Putnik received reports about the fighting around Mačkov Kamen too late, which prevented him from issuing timely orders.

The Battle of Kolubara

On the eve of the Battle of Kolubara, the Serbian army numbered 253,884 men, 426 guns, and 180 machine guns, while Austro-Hungary, within the Balkan Army, had about 300,000 men and 600 guns at its disposal.

When the retreat and abandonment of Belgrade were ordered, Putnik was urged and pressured not to do so, and he then gave perhaps the best description of the capital’s position, saying: “It is not my fault that the capital was placed where a border guard post should be.”

Primarily thanks to Putnik’s command, the Battle of Kolubara was won with the liberation of Belgrade on December 15, 1914.

A total of 42,215 soldiers and NCOs, 323 officers, 142 guns, and 2 aircraft were captured.

During the Battle of Kolubara, Duke Putnik led the Serbian army through its greatest trials.

The enemy, however, was superior, and in 1915 the Serbian army retreated. In November of that year, Putnik had only two options—capitulation or withdrawal across the Albanian and Montenegrin mountains toward the Albanian coast.

He chose withdrawal and on November 25, 1915, in Prizren, issued his last order.

Due to illness he could not move, so an improvised stretcher in the form of a military guard post was made for him, carried by four soldiers.

He was dismissed from the position of Chief of Staff of the Supreme Command on December 8, 1915, and Duke Petar Bojović was appointed in his place.

He recovered on Corfu and suffered from loneliness, and the news of his dismissal he received in February 1916 from the paymaster, who did not pay him the allowance that belonged to him as Chief of the Supreme Command.

“I suffered greatly and was greatly tormented. But I forgive everything—I forget everything. What pains me is only that I was removed from the position of Chief of Staff of the Supreme Command in such a way, as I would not have sent even my worst orderly back to headquarters. Yes, not even an orderly does a good officer dismiss from himself like this and in this manner. And me—me above all—they removed as the worst, because someone had to pay the price. And that pains me—and will pain me until the grave,” said Duke Putnik at the time.

He remained on Corfu until September 1916, when he was transferred to Nice, where he soon died.

The mortal remains of Duke Putnik were not transferred to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia for a full 10 years, prompting protests by surviving soldiers and his students.

A coffin with the mortal remains of Duke Radomir Putnik arrived in Belgrade on November 6, 1926. He was buried at the New Cemetery, and all of Belgrade took to the streets, with many coming to the funeral from Vojvodina and other parts of Serbia.

Legacy

Putnik had a great influence on the development of the Serbian armed forces.

He quickly realized that liberation from the Turks could not be fully achieved through imposed reforms and hatt-i sharifs, but only through armed struggle, and therefore began preparations.

He was the first second lieutenant in history to write a manual for troop training. He decided on this step in 1868. From that year onward, his influence on the development of the Serbian armed forces is noticeable.

He published several books on the art of war and military service.

Putnik made decisions of fateful importance for the Serbian people and the state and proved to be an unsurpassed strategist and a major historical figure equal to the time and trials that befell him.

He was prudent and difficult to throw off balance.

He believed that waging war was a matter for both statesmen and commanders, and he never carried out a decision without obtaining the government’s consent.

Privately, he was a calm, reserved, and modest man.

He avoided appearing adorned with decorations and said that “his decorations are beneath the uniform.”

In Belgrade, a boulevard and an elementary school are named after Duke Putnik, and in Canada a mountain has been named Putnik after the famous Serbian duke.

MORE TOPICS:

MARK BRNOVIĆ BURIED IN PHOENIX: Family and Friends Pay Their Final Respects! (VIDEO)

Source: Mondo, Foto: Wikimedia Creative Commons